|

The

oldest known lens was found in the ruins of ancient

Nineveh and was made of polished rock crystal, an

inch and one-half in diameter. Aristophanes in "The

Clouds" refers to a glass for burning holes in

parchment and also mentions the use of burning

glasses for erasing writing from wax tablets.

According to Pliny, physicians used them for

cauterizing wounds.

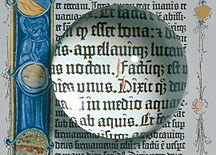

Around1000 A. D. the reading stone, what we know as

a magnifying glass, was developed. It was a segment

of a glass sphere that could be laid against reading

material to magnify the letters. It enabled

presbyopic monks to read and was probably the first

reading aid. The Venetians learned how to produce

glass for reading stones, and later they constructed

lenses that could be held in a frame in front of the

eyes instead of directly on the reading material.

|

|

|

|

Medieval Reading Stone |

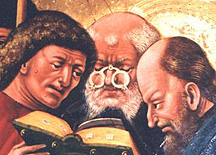

Tommaso di Modena Painting, 14th C. |

Eyeglasses, circa 18th centuy |

The Chinese are sometimes given credit for

developing spectacles about 2000 years ago--but

apparently they only used them to protect their eyes

from an evil force . In the year 1268, Roger Bacon,

the English philosopher, wrote in his Opus Majus:

"If anyone examine letters or other minute objects

through the medium of crystal or glass or other

transparent substance, if it be shaped like the

lesser segment of a sphere, with the convex side

toward the eye, he will see the letters far better

and they will seem larger to him. For this reason

such an instrument is useful to all persons and to

those with weak eyes for they can see any letter,

however small, if magnifier enough". In 1289 in a

manuscript entitled Traite de con uite de la famille,

di Popozo wrote: "I am so debilita-ted-by age that

without the glasses known as spectacles, I would no

longer be able to read or write. These have recently

been invented for the benefit of poor old people

whose sight has become weak". Thus it appears that

the first spectacles were made between 1268 and

1289. In 1306 a monk of Pisa delivered a sermon in

which he stated: "It is not yet twenty years since

the art of making spectacles, one of the most useful

arts on earth, was discovered. 1, myself, have seen

and conversed with the man who made them first". The

name of the true inventor of eyeglasses remains lost

in obscurity.

The first known

artistic representation of eyeglasses was painted by

Tommaso da Modena in 1352. He did a series of

frescoes of brothers busily reading or copying

manuscripts. one holds a magnifying glass but

another has glasses perched on his nose. Once

Tommaso had established the precedent, other

painters placed spectacles on the noses of all sorts

of subjects, probably as a symbol of wisdom and

respect. (See Crivelli's painting of St. Peter) From

the 14th century, painters also presented portraits

of St. Lucy, often carrying her own eyes--they even

appeared as lorgnette-like glasses on a stem.

One of the most significant developments in

spectacle making in the 16th century was the

introduction of concave lenses for the nearsighted.

Pope Leo X, who was very shortsighted, wore concave

spectacles when hunting and claimed they enabled him

to see better than his companions.

The first spectacles had quartz lenses because

optical glass had not been developed. The lenses

were set into bone, metal or even leather mountings,

often shaped like two small magnifying glasses with

handles riveted together typically in an inverted V

shape that could be balanced on the bridge of the

nose. The use of spectacles spread from Italy to the

Low Countries, Germany, Spain, and France. In

England a Spectacle Makers Company was formed in

1629; its coat of arms showed three pairs of

spectacles and a motto: "A blessing to the aged".

From the moment they were invented, glasses posed a

problem that wasn't solved for almost 350 years: how

to keep them on! For all its developmental changes

over the years, the spectacle frame is one of

technology's best examples of poor engineering

design. It virtually teems with defects. The center

of gravity and center of rotation are too far

forward to keep the lenses in optimal position.

Frames depend far too much upon noses, which vary in

size, shape and firmness, and upon ears, which vary

in symmetry, in contour of cartilagenous support,

and in the amount of hair interposed between frame

and ear. They require that the lens plane be

perpendicular to the visual axis, yet this is

geometrically possible for only one direction of

gaze--all other directions will induce changes in

spherical and cylindrical power.

They require that the optical center of each lens be

supported directly in front of the center of each

pupil, but this is manifestly impossible since the

eyes are constantly moving, altering in version and

vergence.

Spanish spectacle makers of the 17th century

experimented with ribbons of silk that could be

attached to the frames and then looped over the

ears. Spanish and Italian missionaries carried the

new models to spectacle wearers in China. The

Chinese attached little ceramic or metal weights to

the strings instead of making loops. In 1730 a

London optician named Edward Scarlett perfected the

use of rigid sidepieces that rested atop the ears.

This perfection rapidly spread to the continent.

In 1752 James Ayscough advertised his latest

invention--spectacles with double hinged side

pieces. These became extremely popular and appear

more often than any other kind in paintings, prints,

and caricatures of the period. Lenses were made of

tinted glass as well as clear.Ayscough felt that

white glass ligives an offensive glaringlight, very

prejudicial to the eyes, and on that account, green

and blue glasses have been advised...". In Spain in

1763 Pablo Minguet recommended turquoise, green, or

yellow lenses but not amber or red.

European men and women, particularly the French,

were self-conscious about wearing glasses. Parisian

aristocrats used reading aids only in private. The

gentry of England and France used a "perspective

glassig or monocular which could be hidden from view

easily. In Spain, however, spectacles were popular

among all classes because people thought glasses

made them look more important and dignified.

Far-sighted or aging colonial Americans imported

spectacles from Europe. Spectacles were mainly for

the affluent and literate colonists, who required a

valuable and treasured appliance. Glasses cost as

much as $200 in the early 1700's. The Boston Evening

Post of 1756 carried an advertisement: "Just

imported in the Scow Two Brothers, Cpt Marsden, from

London and to be sold by Hannah Breintnall at the

Sign of the Spectacles, in Second-Street near

Black-Horse-Alley". Francis McAllister opened his

store in Philadelphia in 1783 with "a bushel

basketfull" of spectacles, through which presumably

his customers could pick and choose.

Benjamen Franklin in the 1780's developed the

bifocal. Later he wrote, "I therefore had formerly

two pairs of spectacles, which I shifted

occasionally, as in traveling I sometimes read, and

often wanted to regard the prospects. Finding this

change troublesome, and not always suffficiently

ready, I had the glasses cut and a half of each kind

associated in the same circle. By this means, as I

wear my own spectacles constantly, I have only to

move my eyes up or down, as I want to see distinctly

far or near, the proper glasses being always ready."

Evidently the idea of bifocals had already been

experimented with in London as early as 1760

(possibly by Franklin himself, who was there at the

time) though never used extensively.

Bifocals progressed little in the first half of the

19th century. The terms bifocal and trifocal were

introduced in London by John Isaac Hawkins, whose

trifocals were patented in 1827. In 1884 B. M. Hanna

was granted patents on two forms of bifocals which

become commercially standardized as the "cemented"

and "perfection" bifocals. Both had the serious

faults of ugly appearance, fragility, and

dirt-collection at the dividing line. At the end of

the 19th century the two sections of the lens were

fused instead of cemented, an idea originated by de

Wecker in Paris and patented in 1908 by Borsch. At

the turn of the 20th century, there was a

considerable increase in the use of bifocals.

Between 1781 and 1789 silver spectacles with sliding

extension temples were being made in France; a pair

owned by Franklin is dated 1788. But it was not

until the nineteenth century that they gained

widespread popularity. John McAllister of

Philadelphia began manufacturing spectacles with

sliding temples containing looped ends which

afforded much easier manipulation with the

then-popular wigs. The loop supplemented the

inadequacy of stability by affording a means for the

addition of a cord or ribbon which could be tied

behind the head, thus holding the spectacles more

firmly in place.

In 1826, William Beecher came to Southbridge,

Massachusetts from Connecticut to establish a

jewelry-optical manufacturing shop. The first

ophthalmic articles he produced were silver

spectacles which were later followed by blue steel.

In 1869 the American optical Company was

incorporated and absorbed the holding of William

Beecher. In 1849 J. J. Bausch emigrated to the

United States from Germany. He had already served an

apprenticeship as an optician in his native land and

had found work in Berne. His compensation for the

labor on a complete pair of spectacles was equal to

six cents. Mr. Bausch encountered difficult times in

America from 1849 until 1861, at which time war

broke out. When the war prevented importation of

frames, demand for his hard rubber frames zoomed.

Continuous expansion followed and the large Bausch

and Lomb Company was formed.

The monocle, which was first called an "eye ring",

was introduced in England about 1800; although it

had been developed by a German during the 1700's. A

young Austrian named J. F. Voigtlander (same family

as the camera people) studied optics in London and

took the monocle idea home with him. He started

making monocles in Vienna about 1814 and the fashion

spread and took particularly vigorous root in

Germany and in Russia. The first monocle wearers

were men in society's upper classes, which may

account for the aura of arrogance the monocle seemed

to confer on the wearer. After World War I, the

monocle fell into into disrepute, its demise

hastened no doubt, by its association with the

German military.

The lorgnette, two lenses in a frame the user held

with a lateral handle, was another 18th century

development (by Englishman George Adams). The

lorgnette probably developed from the

scissors-glass, which was a double eyeglass on a

handle.Since the two branches of the handle came

together under the nose and looked as if they were

about to cut it off, they were known as

binocles-ciseaux or scissors glasses. The English

changed the size and form of the scissors-glasses

and produced the lorgnette. The frame and handle

were frequently artistically embellished, since they

were used mostly by women and more often as a piece

of jewelry than as a visual aid. The lorgnette

maintained its popularity with ladies of fashion,

who would not wear spectacles. The lorgnette was

still popular at the end of the 19th century.

Pince-nez are believed to have appeared in the

1840's, but in the latter part of the century there

was a great upsurge in the popularity of the

pince-nez for both men and women.There was an

enormous variety of styles available. Gentlemenwore

any style which suited them--heavy or delicate,round,

or oval, straight, or drooping--usually on a

ribbon,cord, or chain about the neck or attached to

the lapel.Ladies more often than not wore the oval

rimless style on a fine gold chain which could be

reeled automatically into a button-size eyeglass

holder pinned to the dress. Whatever the

disadvantages of the pince-nez, it was convenient.

In the 19th century the responsibility of choosing

the correct lens lay, as it always had, with the

customer. Even when the optician was asked to

choose, it was often on a rather casual basis.

Spectacles were still available from travelling

salesmen. J. C. Bloom, writing in 1940, described

the method of fitting glasses in the Western part of

the United States in 1889, when he first went into

practice: "When a person came in to get a pair of

glasses, you would look him over, ask his age, and

then reach into one of the boxes that had the

mounted goods and you would-reach from box to box

until the patient said he could see. He would ask

what the price was, and it was anywhere from $150 to

$5." A short paragraph in the "Optical Journal" of

1901 warned that itinerant peddlers were as

troublesome as ever: "If you value your eyesight,

you will place no confidence in the statements of

tramps who go from house to house selling

spectacles. They will tell you your eyes are

diseased and nothing but their electric or

magnetised glasseswill save you from blindness. Such

talk is an insultto your intelligence." Insulting or

not the peddlers evidently succeeded in selling

their wares, as they had for centuries.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Dr. Norburne

Jenkins wrote in the "Optical Journal": "Wearing

spectacles or eyeglasses out of doors in always a

necessity .... Glasses are very disfiguring to women

and girls. Most tolerate them because they are told

that wearing them all the time is the only way to

keep from having serious eye trouble. If glasses are

all right, they will seldom or never have to be worn

in public". Despite this statement, a variety of

glasses and optical aids were available and were

worn in public. Spectacles with large round lenses

and tortoise shell frames became the fashion around

1914. The time had now come when "the average human

disfigurement, often an injury, seldom a person,

instead of being ashamed that his eyes are on the

blink, actually seems to be proud of it". The

enormous round spectacles and the pince-nez

continued to be worn in the twenties. In the

thirties there was increased emphasis on style in

glasses with a variety of spectacles available. Meta

Rosenthal wrote in 1938 that the pince-nez was still

being worn by dowagers, headwaiters, old men, and a

few others. The monocle was worn by only a minority

in the United States. Sunglasses, however, became

very popular in the late 30's.

Contact Lenses

As early as 1845 Sir John Herschel suggested the

idea of contact lenses, though he evidently did

nothing about it. The practical application of a

lens to the eyeball did not occur until late in the

century, when F. E. Muller, a German maker of glass

eyes, blew a protective lens to place over the

eyeball of a man whose lid had been destroyed by

cancer. The patient wore the lens until his death,

twenty years later, without losing his vision. The

term contact lens originated with Dr. A. Eugen Fick,

a Swiss physician, who in 1887 published the results

of independent experiments with contact lenses. In

1889 August Muller, a German medical student,

described his own experimentation with contact

lenses. Although his attempts to use ground lenses

were not successful, he did help lay the groundwork

for further experimentation. In 1892 other doctors

and optical firms in Europe cooperated in developing

practical contact lenses; before long several firms

began specializing in manufacturing them. By the

early 40's a variety of contact lenses was

available: blown glass, ground glass, molded glass,

plastic and glass, and all plastic. All were still

comparatively large and could not normally be

tolerated for long periods of time. Improvements in

manufacturing, material, and fitting of contact

lenses lead to increased numbers of Americans

wearing them. By 1964 over 6 million people in the

United States were wearing contact lenses, 65% of

them female.

back

to top |